🤙🏼 Want to connect? Add me on LinkedIn. 🙏🏼 Not subscribed to the LEVITY podcast on Youtube yet? Do it here. 🎧 More of a listener? The LEVITY podcast is also available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and other places.

Why vitrifixation offers a credible path to halting death

When people ask why I’ve signed up for cryonics, I offer them a few carefully curated arguments.

One of my favorites is a simple thought experiment: Imagine you know you’ll die tomorrow. But your doctor offers you an alternative - instead of death, you can be put into a drug-induced coma for one week, after which there’s a 99 percent chance you’ll wake up healthy, cured of whatever was about to kill you.

My inquisitors usually laugh: “Well, of course I’d take that option. Who wouldn’t?”

Yes, I know, it’s a sinister trap.

And sure, the ifs and buts come quickly after, but in principle, they’ve already answered their own question.

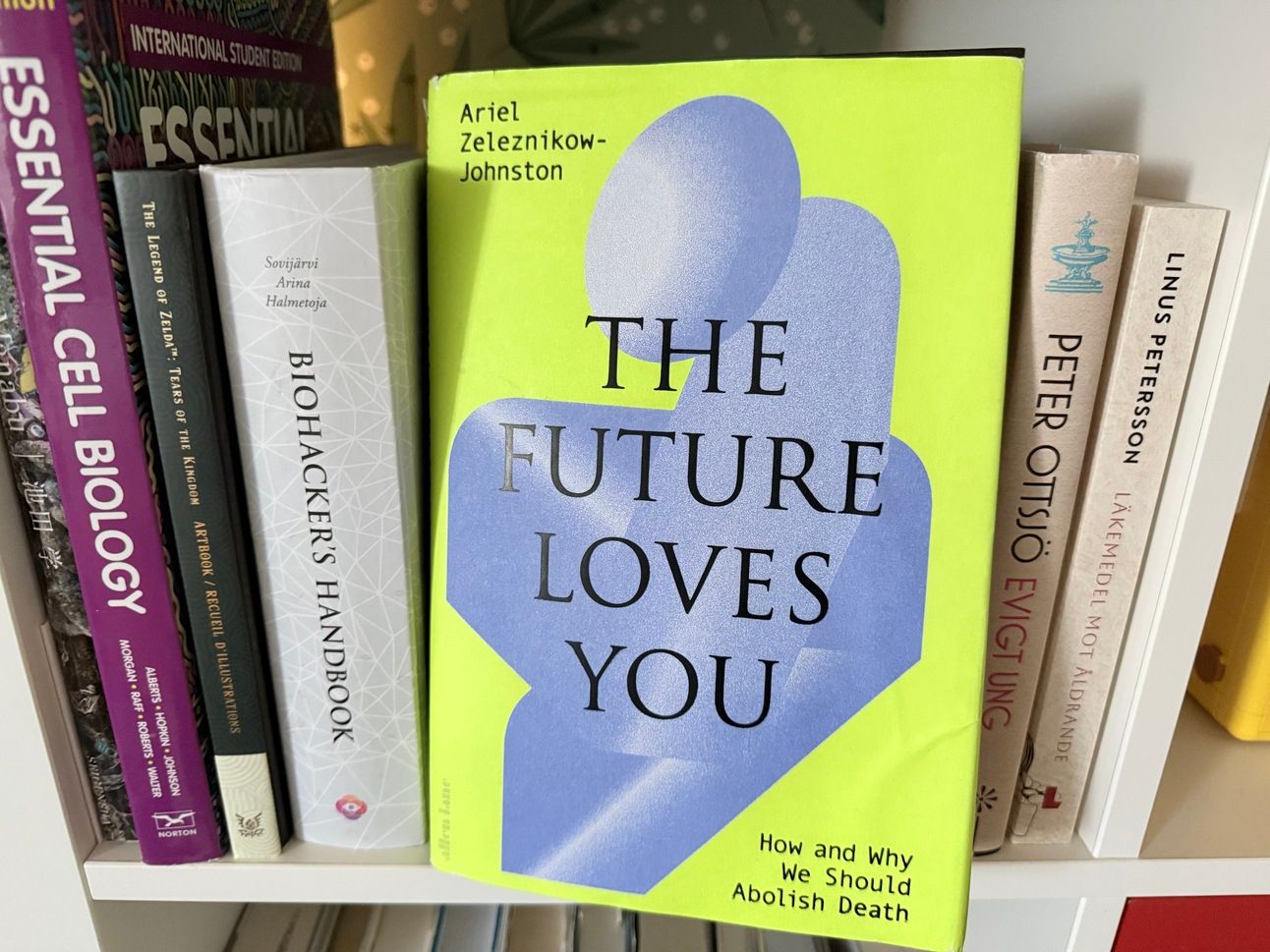

And that’s exactly the kind of mental reset Ariel Zeleznikow-Johnston is pushing for in the brilliant book The Future Loves You - How and Why We Should Abolish Death.

He argues that vitrifixation already offers a scientifically credible way to lock in the connectome’s architecture, holding it intact for as long as necessary until future technologies - whether biological, robotic, or digital - can reanimate or emulate it.

It takes the core intuition behind that thought experiment - that most people, when faced with the choice, would choose the chance to go on living - and extends it into a full-blown scientific, philosophical, and economic case for brain preservation.

Upgrade to LEVITY Premium for full access

Become a paying subscriber of LEVITY Premium to get access to this post and other Premium-only content.

UpgradeA Premium subscription gets you:

- Exclusive content

- Full access to the archive

- Ad-free experience

- My gratitude